“Traditionally, power was what was seen, what was shown, and what was manifested...Disciplinary power, on the other hand, is exercised through its invisibility; at the same time it imposes on those whom it subjects a principle of compulsory visibility. In discipline, it is the subjects who have to be seen. Their visibility assures the hold of the power that is exercised over them. It is this fact of being constantly seen, of being able always to be seen, that maintains the disciplined individual in his subjection. And the examination is the technique by which power, instead of emitting the signs of its potency, instead of imposing its mark on its subjects, holds them in a mechanism of objectification. In this space of domination, disciplinary power manifests its potency, essentially by arranging objects. The examination is, as it were, the ceremony of this objectification.”

― Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison

0

power forms feline, telescopic eyes

these eyes do not glow with a calming light

they emanate insidious neon

these eyes burn through us like needles in dreams

their coded meanings can't be deciphered

these eyes are sly. knowing, omnipresent

they're now embedded in millions of screens

these eyes control collective consciousness

they reflect the paranoia of the times

these ever watchful eyes remain unseen.

power is forming polished programmed worlds

yet we cannot fathom their cold steel depths

we only perceive surface processions

we move like cattle along life's treadmill

unlike saint paul, we will not be reborn

there will be no sudden flash from heaven;

no profound pathways towards flowered dawns

for the scales will not fall from our own eyes

this bleak age has buried transcendent

these ever watchful eyes remain unseen.

1

foucault’s 1975 book in french was entitled surveiller et punir: naissance de la prison, literally translated, ‘surveil and punish: the birth of the prison.’ of all of foucault’s books, this one has received the most attention from educationists. although the book is a history of penal systems, it is also among the few places in which foucault writes explicitly, and in some detail, about schooling.

the opening paragraphs of discipline and punish contain some of the most sensational images ever to appear in a scholarly book: a graphic description of the gruesome torture of robert-francois damiens, who was convicted of attempting to assassinate king louis xv of france in 1757. this description of the torture and execution of damiens in the introduction serves at least two purposes:

- 1 it grabs the reader and evokes in us a visceral awareness of how savage and brutal we humans can be.

- 2 it illustrates an obsolete judicial practice, thereby setting up a historical contrast between older forms of punishment and current forms of discipline.

the main purposes of discipline and punish are to 1) provide a historical argument showing many of the ways humans have devised to enforce regulations, and 2) provoke us to re-examine the disciplinary forms of punishment that we have come to take for granted as humane and enlightened forms of governance. the book is divided into three main sections that give labels to different historical modes of enforcing regulations: torture, punishment, and discipline.

2

torture

in

part 1,’ torture’, foucault cited laws and ordinances to trace changes in practices of punishment from the seventeenth through the nineteenth centuries. in the seventeenth century, foucault explained, torture was ‘not an extreme expression of lawless rage’ (1975, p. 33), but

a technique that was deliberate and calculated: ‘torture rests on a whole quantitative art of pain’ (p. 34). calling attention to ‘the spectacle of the scaffold,’ foucault argued that the function of seventeenth-century torture was (in part) as a means by which the king’s power could be re-established as authoritative. the public aspect of torture was

an exercise in sovereign power. in foucault’s analysis, torture is not an expression of primitive brutality, but a calculated and reasonable mechanism given the aims of government.

a large portion of foucault’s argument in this book is focused on the relationship between torture and the production of truth. in describing eighteenth-century punishments, foucault emphasized the practice of ‘judicial torture,’ the infliction of pain to coerce the accused into telling the truth. in judicial torture, ‘it is as if investigation and punishment had become mixed’ (p. 41). between 1670 and 1775, an entirely new way of thinking about punishment had evolved. eighteenth-century punishment was no longer about reasserting the power of the king by staging public rituals of pain and torture. rather, there was a ‘more equivocal attitude’ about punishment in which the state enforced its laws through torture, and at the same time concealed those acts while rationalizing them in terms of social justice. punishment had begun to require political justification beyond the sworn allegiance to a king.

at the end of this first section on torture, foucault illustrated yet another shift in ways of thinking about punishment indicated by the development of ‘a whole new literature of crime.’ in the nineteenth century, it became possible to think about a crime as `glorious’ and a criminal as a ‘genius.’ citing trends in literature and government statements (called `broadsheets’), foucault noted that punishment had moved from a physical struggle to an intellectual struggle between the criminal and the investigator.

3

punishment

in part 2 of the book, ‘punishment,’ foucault traced more dimensions of changes in the history of punishment, emphasizing at first the shift

from violent punishment to intervention. calling this ‘the shift

from the criminality of blood to the criminality of fraud,’ foucault pointed out that increased wealth and productivity were accompanied by an increased emphasis on crimes against property, and increased efficiency in the techniques of investigation and punishment. he explained the rise of intervention techniques as a self-perpetuating cycle:

following a circular process, the threshold of the passage to violent crimes rises, intolerance to economic offences increases, controls become more thorough, penal interventions at once more premature and more numerous. (p. 78)

the shift from punishment to intervention accompanied economic and political rationalities that were instituted to prevent wrongdoings. one of the most revealing parts of this section is foucault’s lengthy quotation of joseph michel antoine servan (1737-1807), a french journalist. servan wrote:

a stupid despot may constrain his slaves with iron chains; but a true politician binds them even more strongly by the chain of their own ideas; it is at the stable point of reason that he secures the end of the chain; this ink is all the stronger in that we do not know of what it is made and we believe it to be our own work; despair and time eat away the bonds of iron and steel, but they are powerless against the habitual union of ideas. (p. 103)

4

the gentle way

after quoting servan, foucault explained another mode of punishment as ‘the gentle way.’

‘the gentle way in punishment‘ is a description of trends that shifted the purpose of punishment away from redeeming the sovereign or reforming the criminal, and towards a mechanism for administering society at large. punishment began to take on a purpose that extended beyond the criminal to have an effect on innocent, non-involved people. these days, we call that aspect of punishment a deterrent. in foucault’s words, ‘how did the coercive, corporal, solitary, secret model of the power to punish replace the representative scenic, signifying, public, collective model?’ (p. 131).

this is a turning point for foucault’s argument in discipline and punish. in the quotation from servan, we can begin to detect foucault’s definition of disciplinary power. by highlighting this historical addition to the intended effect of punishment, namely from punishing guilty to deterring the innocent, foucault laid the groundwork for the rest of the book that explains how punishment took on another modality, namely discipline.

5

discipline

‘discipline,’ the title of part 3 of discipline and punish, is comprised of three sections. the first two, ‘docile bodies’ and ‘the means of correct training,’ contain the bulk of foucault’s explicit writing about schooling and education. in these sections, foucault focused primarily on five aspects of education: the architecture of the classroom; the timetable; the pedagogization of learning; the organization of people into institutional roles; and examination techniques. below are brief descriptions of each of those five aspects of education, according to discipline and punish.

foucault described the architecture of eighteenth-century schools as enclosures separated by partitions and organized to promote supervision, work, and hierarchy. since this is the kind of classroom with which we are most familiar, it might be difficult to imagine any alternative. however, we can begin to imagine an alternative if we remember the writings of jean-jacques rousseau (1712-1778), a swiss philosopher. in his famous book, emile (1762), rousseau advocated an approach to education in which children would be allowed to pursue their own natural curiosity using their god-given rational faculties by traveling in the company of a wise and sympathetic adult who acted as a protector and resource of information for the child. rousseau’s approach to education criticized the enclosed, partitioned, organized classroom saying that such regimented classrooms tended to perpetuate all the weaknesses of aristocratic and bourgeois civilization.

6

pedagogization

foucault described the architecture of schools to highlight how enclosures and partitions, by regulating people’s movements, serve as disciplinary mechanisms. among other things, enclosed, partitioned classrooms prevent spontaneous gatherings and unsupervised wandering, and in that way the architecture is an intervention to prevent wrongdoings. the purpose of mentioning rousseau’s emile here is to emphasize that the enclosed, partitioned, organized classroom is not the only way schooling can be conceived.

the timetable is the second aspect described by foucault as a disciplinary feature of schooling. like the enclosed classroom architecture, timetables also regulate people’s actions with the intention of preventing wrongdoings. like military organization, school timetables serve as disciplinary mechanisms:

a sort of anatomo-chronological schema of behaviour is defined. the act is broken down into its elements; the position of the body, limbs, articulations is defined; to each movement are assigned a direction, an aptitude, a duration; their order of succession is prescribed. time penetrates the body and with it all the meticulous controls of power. (p. 152)

the ‘pedagogization of learning’ is another aspect of schooling we tend to take for granted, and foucault called this into question as well.

‘pedagogization’ refers to the ways school learning is separated from adult life and organized into developmental sequences that are assumed to be understandable by children. foucault contrasted this pedagogization of learning with the previous practices in guilds where learning occurred between masters and apprentices. in guilds, apprentices learn from masters in sites where adult work actually takes place. schools change that. in schools, the adult world is only simulated. a school approach to learning takes on a particular sequence that is regulated and mediated by (psychological and moral) assumptions about children.

schooling consists of a series of exercises, and as such, this specified sequence serves to discipline people. in foucault’s words:

exercise is a technique by which one imposes on the body tasks that are both repetitive and different, but always graduated. by bending behaviour towards a terminal state, exercise makes possible a perpetual characterization of the individual either in relation to this term, in relation to other individuals, or in relation to a type of itinerary. (p. 161)

the fourth aspect of educational discipline is the organization of people into functional roles. here, foucault gave the example of the famous ‘peer tutoring’ method that was instituted by joseph lancaster in his london school in 1798. in the lancaster approach to schooling, older students were in charge of younger students, imposing order and enforcing rules on them. the lancaster approach instituted a chain of command, a hierarchy of accountability and responsibility according to age. in that way, the students were not an undifferentiated mass; they were organized into ranks that aligned with the school’s purpose of maintaining order and discipline.

7

docile bodies

in the lancaster approach, the organization of students into ranks facilitated

the development of what psychologists now call ‘conditioned responses’ or ‘automaticity.’ with constant monitoring of students by students, there was little flexibility in the classroom for students to behave in any unregulated manner. as foucault’s history tells us,

the degree of regulation in the classroom occurred at minute levels of detail that foucault described as ‘dressage.’ ‘dressage’ is a term from horseback riding; it is the training of horses to respond with precise movements when the rider gives only minimal signals. lancaster’s methods were like dressage. a signal like a bell was used to command the students: a single ring of the bell meant the student should be silent and pay attention to the teacher; two rings meant the student should read aloud to his classmate, and so on. the students were expected to obey the signals immediately. the lancaster method of schooling serves as foucault’s historical example of the ways in which education constructs

‘docile bodies.’

8

the gaze

the last aspect of schooling is described in ‘the means of correct training.’ here, discipline and punish provides historical detail about the function of examinations in schools and hospitals. by ‘examination,’ foucault was not referring only to written tests that measure learning, but to

the practices of schools in which teachers looked into students’ lives to find out what kinds of people they were. this ‘examination’ included written tests of learning, but it also included conduct, posture, attitude, and cleanliness. when we understand ‘examination’ in this way, we can begin to see another of the famous concepts in foucault’s analysis, namely the

‘gaze.’ the gaze refers to the practice of students monitoring students, and students learning to monitor themselves:

the examination in the school was a constant exchanger of knowledge; it guaranteed the movement of knowledge from the teacher to the pupil, but it extracted from the pupil a knowledge destined and reserved for the teacher. the school became the place of elaboration for pedagogy. and just as the procedure of the hospital examination made possible the epistemological ‘thaw’ of medicine, the age of the `examining’ school marked the beginnings of a pedagogy that functions as a science. (p. 187)

in this excerpt we can read foucault’s argument that science and rationality are mobilized in the service of school examinations. examinations, in their turn, are a practice of the monitoring gaze that serves as a mechanism of power in administering people.

one important point to notice about the function of the gaze is that it is very different from torture. in foucault’s description of how students are monitored minute-by-minute in school, we are compelled to notice that the methods of enforcing school discipline do not include torture or the threat of torture. foucault’s question is: without the threat of torture, why do people do as they are told? nineteenth-century discipline in schools is not the same as seventeenth-century enforcement of monarchical authority through the use of public displays of torture, but discipline is nonetheless effective. discipline through the monitoring gaze has been instituted in schools so effectively that people actually comply with rules and regulations.

through these examples of schooling practices, we are struck with the disturbing realization that discipline can be as effective as torture as a means for getting people to behave in a particular way

9

panoptican

moreover, in reading these historical descriptions we may be simultaneously relieved and chagrined to realize the degree to which we view discipline in favorable terms. for most of us, discipline is a good thing, a necessary practice, and a civilized mechanism for administering society. at the point when we accept that discipline is a more civilized mechanism than torture, we have become (what foucault called) ‘normalized.’

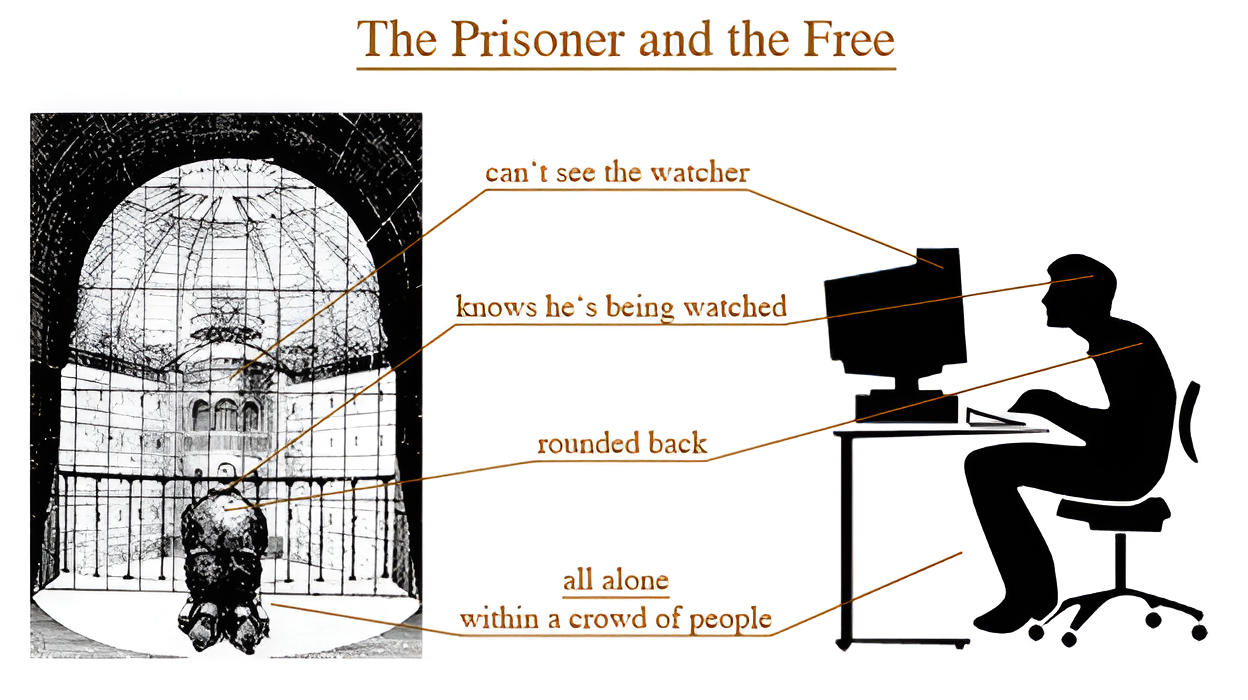

as a way of emphasizing the relationship between surveillance and normalization, foucault ended part 3 with a description (including pictures) of jeremy bentham’s panopticon. bentham (1748-1842) was an english philosopher who was known as a social reformer and defender of human rights. as part of his social reform, he drew the blueprint for a new architectural design for a prison called the panopticon. the panopticon is circular and consists of several levels (storeys). at the center of the panopticon is the guard’s station. at the periphery of the circle are the prisoners’ cells. the guard can see all the prisoners, but the prisoners cannot see the guard. bentham’s speculation was that the prisoners would never know when they were being watched, and therefore they would behave properly all the time whether they were being watched or not.

10

prison

it was this last part, ‘whether they were being watched or not,’ that became an item of intrigue for foucault.

the feature of the invisible watchman is at the heart of foucault’s theory of discipline as normalization: we behave in a particular way whether we are being watched or not. the threat of torture is not necessary; even the posted guard is not necessary. we discipline ourselves for better or worse; and to the degree that we accept our discipline as natural, we have become normalized.

__________

if we are not being threatened by torture, and we do not know whether we are being watched, then what are the regulatory mechanisms in place that explain the processes of normalization? in part 4 of discipline and punish, ‘prison,’ foucault specified ‘seven universal maxims’ of the prison. these are the mechanisms of regulation in prisons:

1 correction

2 classification

3 modulation of penalties

4 work as an obligation and a right

5 penitentiary education

6 technical supervision

7 auxiliary institutions

we can read into foucault’s analysis here the literary device of parallelism. the principles of prisons listed in part 4 are presented as parallel to the principles of schools outlined in part 3. because the analysis of prisons is presented as parallel to the analysis of schools, we are invited to imagine a relationship between schools and prisons. however, the relationship between prisons and schools is not metaphoric; we are not supposed to conclude that schools are like prisons. rather, in foucault’s analysis, the relationship is that schools and prisons both emerged under the same historical conditions. the mechanisms of governance – as reflected in both prisons and schools – multiplied in dimension over time to include torture, punishment, and discipline.

11

even as we imagine a relationship between schools and prisons, it is important

not to misread this relationship as a simple correspondence. it would be a mistake to understand foucault’s meaning to be that schools incarcerate people as prisons do, or that both schools and prisons somehow thwart human freedom. the argument in discipline and punish is more subtle and nuanced than that. foucault’s historical analysis does not conclude that prisons gradually became less brutal and more civilized as they abolished torture and replaced it with discipline. it does not conclude that discipline is the antithesis of freedom. it does not conclude that the mechanisms of discipline in schools were a step toward progress in the civilizing process.

rather, the analysis suggests that each of these penal modes – torture, punishment, and discipline – had its own logic, its own system of reasoning, and its own mechanisms of practice that made sense for their time. furthermore, it is not so certain any more that torture is less onerous than discipline. when you read foucault’s graphic descriptions of disciplinary practices, you may find yourself entertaining the suspicion that the designs of school enclosures, the rigid timetables of classes, and the lockstep routines may not, after all, be completely free of the inhumanity demonstrated by the burning and dismemberment of damiens.